To Understand Jio, You Must Understand Reliance

Author Byrne Hobart | October 3rd, 2022

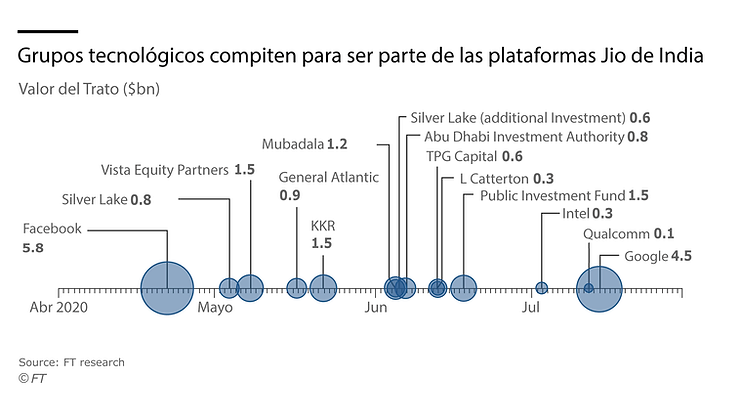

In late April, Facebook made an unusual announcement: It was investing $5.7 billion in the Jio Platforms subsidiary of Reliance, an Indian telecommunications company with 398 million subscribers. This kicked off an impressive run of investments:

And that's not all: Amazon.com is in talks to make an investment in Reliance retail.

The only remotely comparable funding streak was Uber's fundraising sprint between 2014 and 2016, when they received checks from Blackrock, Google, KPCB, Menlo, Sherpa, Summit, Wellington, Qatar's sovereign wealth fund, Valiant, Lone Pine, NEA, Baidu, Goldman, Times Internet, Foundation, Microsoft, Tata, Tiger Global, T. Rowe, Saudi Arabian sovereign wealth fund and Softbank. If you were in a position to write checks for $100 million or more in 2014-2016, there was a good chance you would write one to Uber. And if you could write the same kind of checks in 2020, you probably wrote one to Jio.

Jio's business has been well covered on some sites. There was good feedback from Bens Evans and Thompson ($). The basic story is that Jio made a huge capital investment ($32 billion as of 2018) in a network designed for both data and voice. They charge for data and voice is free. A good framework for understanding successful tech companies is that they spend whatever it takes to stay with a significant amount of economic activity, then identify which parts of it create the most value and gradually take over. US telecommunications companies tried to do this in the early 1990s, with several interactive TV companies failing, and the big winners turned out to be companies operating on the open platform of the Internet. But each situation is unique; Jio can borrow proven ideas and offer them on its platform, and—as Facebook noted in its investment press release—it can connect local shoppers with merchants and instantly create one of the largest mobile payment platforms in the world. world.

At the Jio level, the deal makes sense. It coincides with Naspers' investment in Tencent, albeit at a more advanced stage: owning a piece of The Everything Platform in a country with a billion people and a growing economy has historically been a good bet.

But there is another interpretation: the agreement has to do in part with Jio, but also with Reliance. Investors bought Jio because it has good metrics and a great story. But Reliance sold because it had promised to reduce its debt, and a deal with Saudi Aramco didn't work out on time ($). Reliance, as it turns out, is a fascinating company, and a great look at the way countries develop. Jio's deals reflect a long tradition at the company, which has three comparative advantages: risk tolerance, financial engineering excellence, and an incredible ability to optimize around regulations or optimize regulations around Reliance.

In the early 1950s, Yemen's monetary authorities noted a worrying trend: currency shortages. After investigating the matter, they met a young clerk from the city of Aden, who had discovered that, at the prevailing exchange rate, the Yemeni rials contained more silver than their face value. So he bought them for sterling, melted them into silver, exchanged the silver for pounds, and repeated the process. That employee, Dhirubhai Ambani, soon left Aden to return to his native India, where he founded Reliance.

This is the first business anecdote to be told in the endearing book The Prince of Polyester, a book with enough amusing anecdotes about Ambani's business career that it got banned after publication.

Most of the stories in the book are like that. Ambani identified a discrepancy between the model of reality implicit in government regulations and the actual state of the world. He turned it into an arbitration. And he blew it up.

For example, in the 1950s and 1960s, Reliance made a market in an interesting asset class: import permits. At the time, India's protectionist policy only allowed companies to import raw materials in proportion to their exports, but not all exporters needed their quota. So Ambani cornered the yarn import permit market—giving him not just an asset, but the power to turn the supply off and on at will. Monopolizing a commodity is always good, but monopolizing an essential input consumed by manufacturers with high fixed costs is even better; the market Reliance could target was determined not only by what price a monopolist could charge, but by what factory owners would pay to avoid existential uncertainty.

Reliance later benefited from other parts of India's protectionist regime. Their synthetic fiber arbitrage worked like this: To make manufacturers self-sufficient, the Indian government allowed them to import raw materials only in proportion to the products they exported. Ambani convinced the government to allow him to import polyester filament yarn in proportion to the nylon products he exported. Nylon was cheap in India, but polyester filament was 600% more expensive when sourced locally in India than it was when imported. So Ambani set up a closed loop: making nylon clothing from locally sourced materials; sell it abroad; use the import quota to import polyester filament; sell it at home And, just to be sure, he also dealt with the demand side: at least according to The Prince of Polyester, Ambani sent money abroad to buy his own goods at the duty-free ports, then sold them cheaply, he gave away or even threw them into the ocean.

The whole business was ontological arbitrage: "nylon" and "polyester filament thread" were synonymous in law but different in price, and Ambani made money by bridging the gap.

Reliance's timing was amazing: when tariffs went up, Reliance stockpiled the products in question; when their inventories were depleted, tariffs were lowered. It's unclear when the system went from Reliance knowing what the government was going to do to deciding what the government was going to do, but it's clear that at the height of their power they could call the shots.

Reliance's diversification shows the way forward for companies in an overly regulated and corrupt economy. The company started in the import-export business, which requires little capital, and later expanded into synthetic fiber production, clothing retail, and oil refining. When they didn't have much political influence, they couldn't risk buying fixed assets; as they gained more influence, they had a comparative advantage in taking that kind of risk. (It helped that the company's underlying risk tolerance was, at times, extravagantly high: Reliance once smuggled an entire factory into India, one piece at a time.) In a low-trust country, vertical integration makes sense: better to control an entire supply chain than risk a competing oligarch monopolizing a key industry.

India's economy was reformed, first gradually and then, in 1991, suddenly. And Reliance reformed itself, too, in a very interesting way: it went public and acquired a massive investor base. From 1980 to 1985, the number of stock investors in India increased from 1 million to 5 million, and by 1985 one million of them owned Reliance shares. Since stock investors tend to be middle-class and upper-class, this gave Reliance a broader political pool: Rather than buy off individual regulators with kickbacks, they buoyed up the electorate with dividends.

As a public company, Reliance engaged in novel financial engineering—issuing convertible bonds with ambiguous conversion terms, exploiting those terms to raise cash when needed, and, at one point, cornering the market in its own shares. Perhaps the high point of Reliance's financial engineering came in 1986, when the company publicly declared that profits would increase, only to discover that profits weren't increasing after all. The solution: an 18-month fiscal year. Record benefits guaranteed.

Today, Reliance is not the company with swashbuckling histories that it used to be. It is now run by Dhirubhai's son, Mukesh Ambani. It is still huge and influential. Last year, the group's total revenue was $87 billion, or 2.6% of India's GDP. Reliance generates 9% of India's exports. It is the second largest energy company in the world, manages almost 12,000 points of sale and, of course, sells mobile phone services.

Jio is a nice case study in recovery growth. This is how it is supposed to work: a technology is tested in rich countries, which spend more on R&D and have a large middle class that spends freely. The technology is then moved to a poorer country, where a low-cost/low-margin version achieves wide distribution. This has happened incredibly fast – Jio launched in 2016 and today has 398 million subscribers. And much of this was driven by prices. The Information says that before Jio, "many mobile users disconnected their data plans when they left home to avoid accidentally running up high bills." And now Jio users consume 12 GB of data per month at an average monthly cost of $1.82.

Jio's fundraising was timely in two ways: Reliance wanted to deleverage and outside investors wanted to tap into the India market. It is no coincidence that this fundraising came at the same time that tensions with China flared; a country that can ban TikTok and restrict Chinese investment can also do the same for other countries. And, of course, it helps that Jio is getting more liquidity at the same time that its competitors mysteriously found themselves with gigantic fines.

And Jio is also a bid for tech nationalism in another direction: At the Reliance annual meeting, Mukesh Ambani promised:

¨That JIO has designed and developed a complete 5G solution from scratch. This will enable us to launch a world-class 5G service in India... using 100% domestic technologies and solutions. This Made-in-India 5G solution will be ready for trials as soon as 5G spectrum becomes available…and may be ready for field deployment next year.”

It is not just a business decision. Suspicions about Huawei have made 5G a matter of national pride, like having a navy, a state-owned airline, or premium exported beer. Once again, Jio is going all out—and once again, Reliance is building something that foreign competitors will have a legal hard time competing with.

As Vedica Kant has pointed out, Mukesh Ambani used the phrase “data is the new oil” to talk about Jio. As the CEO of a company that owns oil refineries and a data-focused mobile phone operator, he is perhaps the only person in the world qualified to make the comparison with a straight face. But the experience lived by participants in the oil industry depends largely on how expensive it is to extract their oil and how risky their property is. Perhaps a more apt comparison is: Jio is the new Ghawar, an immensely valuable, low-marginal-cost data business whose economic owner exercises substantial control over the government.

The Jio story is actually one more chapter in Reliance's long history of cooperation with the Indian government. As the game changed, Reliance remained an adaptive player: when the economy was heavily regulated and run by unaccountable bureaucrats, they played the bureaucratic game; when regulations were loosened and the government became more responsive to the popular will, Reliance ensured that the population owned many of its actions; And now, as more commerce and government are mediated by smartphones, they've moved quickly to master that, too. A reasonable analogy can even be made to the early days of the yarn trade: India once restricted imports of synthetic fiber, and now it restricts imports of US capital. Once again, Reliance is in the middle, ready to build a business and capture a huge profit margin.